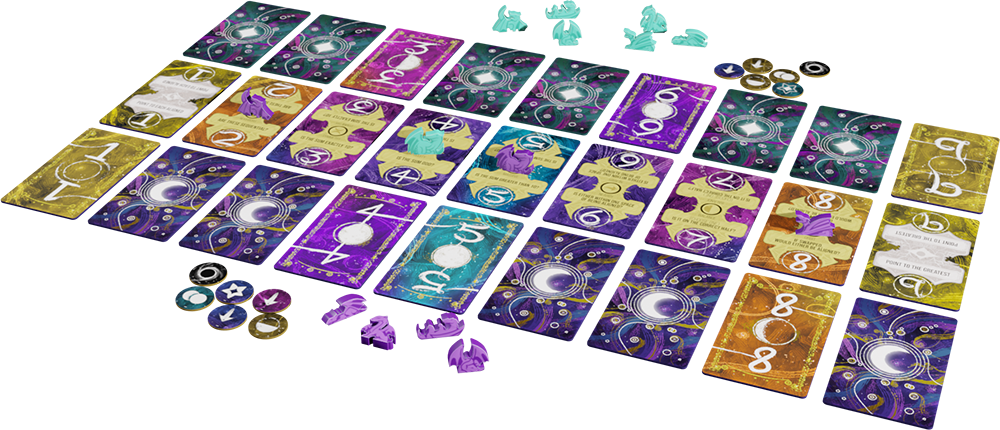

We are proud to have designed Weird Giraffe’s newest game, “Logic & Lore.” You can find the kickstarter for our little cozy-competitive game here: Logic & Lore — Kickstarter

This is the first of several design diary entries. Today we are going to share the game’s origins. And those origins involve Darren and eggs.

“Darren loves breakfast food.” – Darren

Darren brought a design prompt to breakfast one morning before Gencon in 2021. We were going to pitch other games that day, and a little design exercise would be a good diversion before the upcoming grind of pitching games. The prompt was simple: “Here are cards numbered 1-7, a set for each player. Can we make a game about putting them in order? What if they were face-down? Is there a game here? Can the game feature moon phases and use tarot style cards?”

We found the simple direction compelling. We slid around those 14 cards while eating breakfast at “Wild Eggs,” trying to let them speak to us. We talked through a few “what ifs”, but nothing immediately made sense. We had little mechanics like flipping and unflipping cards, “Action Points” the player could spend. Different numbers would let you do specific actions if you chose them. Peeking at your opponent’s cards and rearranging them. Nothing felt solid, so we finished our breakfast and spent the remainder of Gencon learning how to pitch games. It did not go great.

Fast forward six months. We were again eating, this time wings in Cincy (most of our stories involve food), when Darren brought the cards back out, now tarot-sized and celestial themed — with the same goal: Here are simple numbers, put them in order. We still operated from some general assumptions, each player would have 7 cards. Those cards are numbered 1-to-7. You shuffle them up and put them facedown to start. Then, if you get them in order before your opponent does, you win. From chaos to order. Somehow.

This time things clicked! Here were the mechanical breakthroughs we had during that meal:

1) JUST ASKING QUESTIONS: If you can’t see the cards and you need to align them 1-to-7, you need a simple game loop that gets you closer to the solution. What if each turn you held up 2 cards and asked questions about them in relation to one another. Maybe that relationship would give you a lot of information. Why only 2 cards? What if we asked about more than 2 cards? Darren reminded Jason that holding more than 2 cards is difficult. Right, right. 2 cards.

2) ALWAYS BE CLOSING: The second big breakthrough was “what if the questions you asked were actually a waterfall of questions?” A slate of potential things you could learn each turn, a consistent set you could rattle off. That meant that your primary decision point wasn’t “what questions to ask”, but became “which cards to ask about.” This lets the information come to you. But that could still be too much information, so what if the waterfall broke when you received a positive hit? Bite-sized info. Doing that would mean you always gained a bit of information, and the flow was throttled. And if you were clever, you could take advantage of the negative information you received along the way.

We next identified that the waterfall needed an ultimate fail-case question – a simple question that was always useful and importantly always returned a positive. If the other, more obscure, questions in the waterfall failed, at least you would know which card was higher value than the other. This gave the game a much-needed baseline. A drumbeat! You could also play the game and entirely order your cards 1-7 by learning which was higher than the other. This was like Codenames letting you provide clues about 1 card, or like playing Dominion and only buying Silvers and Golds. This gave us a backstop, a worst-case deduction scenario where players could slowly plod toward a solution. But with all of this information and all of these facedown cards, how are players supposed to track it?

3) AVOIDING MEMORY: The next thing we saw was, we didn’t want this to be a memory game. We wanted a deduction game! Sure you could take notes or use tokens to remember what things likely were, but that can’t be it. We learned the next important question to ask of those two revealed cards- Is that card in the right position? Was it aligned? When that was the first question we asked, now you could let players flip it face-up and lock it in but at the cost of learning much about the other cards in the lineup. You could also now see your overall progress and, importantly, you could see your opponent’s progress too. Now the game was a pure race. Who could flip their cards up first? But, oh-oh, now if you were far behind of your opponent you KNEW IT. You knew that you didn’t have enough actions to catch up. We needed to give a trailing player the chance to win. We needed a splash ending. We needed …

4) A MOONSHOT: The last big leap was the idea that you could just win the game whenever you wanted. Or, of course, lose the game. This game wanted to be light and give you some player interaction. What if, at the start of their turn, players could always just turn all of their cards over to win or lose it all? Since you see your opponent’s progress, you might take that risk. And you wanting to take that risk would make your opponent consider taking the same risk. We LOVED that tension. And who doesn’t love a game where you can win or lose on the first turn. We wanted the game to be on the shorter side. You can always just play again.

Those were the four tent poles of the game we called, at the time, Constellé. Four mechanisms that came together to create a very sturdy backbone for the game that’s on Kickstarter now. Along with those core insights, we iterated several more systems into the game that gave players more agency, increased player interaction, and added a ton of replay value. But we’ll discuss those in our next Design Diary.

Thanks for taking the time to read about our little game. We hope you love it.

If you are interested in a Durdle design send us a message through our Contact Page.